JOY, JOY, JOY

.

.

We wish you all of the happiness of the season!

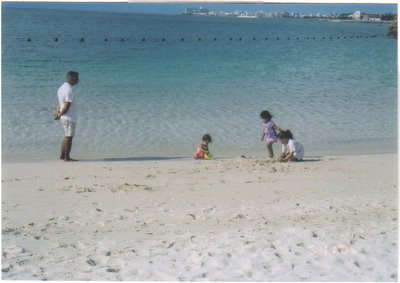

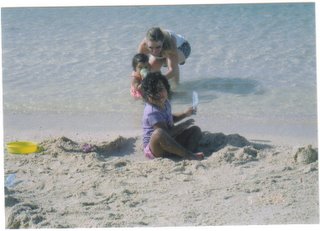

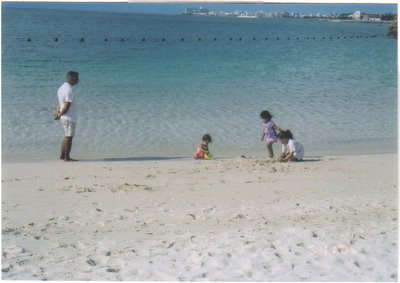

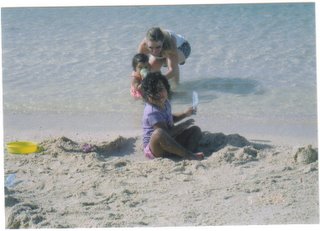

It’s not going to snow in this part of Japan. It may not even get very cold, as former Midwesterners understand cold. This makes it a little hard to believe that the holidays are bearing down on us like an overloaded sled. Last weekend, we spent an afternoon building sandcastles on the beach and trying to explain to our young natural scientists what coral is. Indiana doesn’t care what coral is --- she’s too busy becoming one with the beach. She eats the sand, enthusiastically, face first. She drinks the sea. She stands in the mild surf up to her chin: she’s a happy, beachy baby. Atanasia wants to know the origin of every seashell and coral bit, and examines algae and seaweed minutely. Sebastián spends his time experimenting to find the perfect level of sand dampness for constructing crumble-resistant towers.

Atanasia wants to know the origin of every seashell and coral bit, and examines algae and seaweed minutely. Sebastián spends his time experimenting to find the perfect level of sand dampness for constructing crumble-resistant towers.  He also rescues hapless tiny clams and jointy hermit crabs who find themselves unwelcomely dry. Nobody ever wants to leave, although as we put on our shoes often the youngest young people find themselves completely unable to walk and must be carried home like the princesses they are.

He also rescues hapless tiny clams and jointy hermit crabs who find themselves unwelcomely dry. Nobody ever wants to leave, although as we put on our shoes often the youngest young people find themselves completely unable to walk and must be carried home like the princesses they are.

Indiana has become convinced that being asked to share her Papi with other family members is deeply unreasonable. Apparently, we’re rubbing all of the affection off every time we touch him. So she defends her exclusive rights by yelling indignantly and swatting us with great vigor and accuracy any time any of us comes within arm’s reach. Fortunately she has other things she needs to do, besides being carried around by her Papi and keeping the rest of us love-stealers away, things like seeing how many small toys she can cram into the VCR, and hiding her brother’s toothbrush, and turning off the computer while her siblings are in the middle of a game. Indiana is absolute proof of my theory that you get the child you’re ready for, because if she’d come any earlier we wouldn’t have had time to develop these vast reserves of tolerance for the antics of bright, energetic children. Sebastián is, as always, the most thoughtful and best behaved young man any parent could hope for. Sebastián feels things very deeply, and we worried that this transition would be hard for him, but he’s doing so well! He’s got a great teacher, new friends, a huge playground for recess, and a whole lot fewer teeth than the last time you saw him. He’s even trying new food --- this week he actually said he liked the quiche (which, as any parent of a picky eater will understand, we sensibly renamed “cheese pie”). Beautiful, temperamental Atanasia is also busy being smart as a whip; we’ve been very fortunate with her school, as well. She didn’t want to move to the 4-year-olds’ class when the fall session started, so she’s stayed with the older kids and has already mastered the alphabet and counting to 100, and has moved on to phonics, human anatomy, and addition and subtraction. All three of them are becoming more themselves every day. What more could we wish for our children, or for ourselves?

Health and happiness to you and yours in this season and always!

.

We wish you all of the happiness of the season!

It’s not going to snow in this part of Japan. It may not even get very cold, as former Midwesterners understand cold. This makes it a little hard to believe that the holidays are bearing down on us like an overloaded sled. Last weekend, we spent an afternoon building sandcastles on the beach and trying to explain to our young natural scientists what coral is. Indiana doesn’t care what coral is --- she’s too busy becoming one with the beach. She eats the sand, enthusiastically, face first. She drinks the sea. She stands in the mild surf up to her chin: she’s a happy, beachy baby.

Atanasia wants to know the origin of every seashell and coral bit, and examines algae and seaweed minutely. Sebastián spends his time experimenting to find the perfect level of sand dampness for constructing crumble-resistant towers.

Atanasia wants to know the origin of every seashell and coral bit, and examines algae and seaweed minutely. Sebastián spends his time experimenting to find the perfect level of sand dampness for constructing crumble-resistant towers.  He also rescues hapless tiny clams and jointy hermit crabs who find themselves unwelcomely dry. Nobody ever wants to leave, although as we put on our shoes often the youngest young people find themselves completely unable to walk and must be carried home like the princesses they are.

He also rescues hapless tiny clams and jointy hermit crabs who find themselves unwelcomely dry. Nobody ever wants to leave, although as we put on our shoes often the youngest young people find themselves completely unable to walk and must be carried home like the princesses they are. Indiana has become convinced that being asked to share her Papi with other family members is deeply unreasonable. Apparently, we’re rubbing all of the affection off every time we touch him. So she defends her exclusive rights by yelling indignantly and swatting us with great vigor and accuracy any time any of us comes within arm’s reach. Fortunately she has other things she needs to do, besides being carried around by her Papi and keeping the rest of us love-stealers away, things like seeing how many small toys she can cram into the VCR, and hiding her brother’s toothbrush, and turning off the computer while her siblings are in the middle of a game. Indiana is absolute proof of my theory that you get the child you’re ready for, because if she’d come any earlier we wouldn’t have had time to develop these vast reserves of tolerance for the antics of bright, energetic children. Sebastián is, as always, the most thoughtful and best behaved young man any parent could hope for. Sebastián feels things very deeply, and we worried that this transition would be hard for him, but he’s doing so well! He’s got a great teacher, new friends, a huge playground for recess, and a whole lot fewer teeth than the last time you saw him. He’s even trying new food --- this week he actually said he liked the quiche (which, as any parent of a picky eater will understand, we sensibly renamed “cheese pie”). Beautiful, temperamental Atanasia is also busy being smart as a whip; we’ve been very fortunate with her school, as well. She didn’t want to move to the 4-year-olds’ class when the fall session started, so she’s stayed with the older kids and has already mastered the alphabet and counting to 100, and has moved on to phonics, human anatomy, and addition and subtraction. All three of them are becoming more themselves every day. What more could we wish for our children, or for ourselves?

Health and happiness to you and yours in this season and always!